When Does Religion Start Being Art?

When historical artifacts collide with modern ideologies

Ever tried fixing an old family treasure?

Years ago, in the shadowy corner of our basement stood a majestic armoire, a relic from last century. It was hand-crafted by a great-uncle, a man who turned simple wood into complex stories. This dusty wardrobe, with its rich mahogany scent was more than just furniture — it was an untold family chronicle in timber.

I’m not sure if that great-uncle planned on it being the perfect spot for hide-and-go-seek, but then again, he probably hadn’t read the wonderfully clever religious propaganda series, The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, like I had.

I don’t know where that varnished mahogany cabinet ended up, but I know I wasn’t allowed to let anything bad happen to it as a kid.

No touching, no marking, and, I’m quite sure, no hiding from seekers.

If we had scuffed it up though, I have no doubt a professional would’ve been called in to fix it.

After all, even though the story behind the armoire was short and simple, somehow this object maintained an aura of respect akin to that for our ancestors.

It was made by a former family member, ergo it is precious.

Does your family cherish a similar heirloom?

Maybe it’s a delicate Christmas ornament passed down through generations, a crystal figurine that catches the light just so, or perhaps an old watch from WWII that no one’s allowed to ask Grandpa about until very recently in certain parts of the Southern United States.

Because…reasons.

These objects are more than their material worth; they are the silent witnesses to our families’ journey through time.

A Splash of Color on History’s Canvas

Just like our cherished family heirlooms, sometimes history itself gets an unexpected makeover.

Take a journey to the serene mountains of Sichuan province in China, where a group of ancient Buddhist statues recently found themselves at the center of a colorful controversy.

These statues, carved with the skill and devotion of artisans from the Northern Wei Period (386–534), have stood as silent witnesses to centuries of history. They’ve seen empires rise and fall, and they’ve watched the quiet comings and goings of generations.

Yet, they remained unchanged — until now.

In a well-intentioned but ill-fated effort to express gratitude, the local villagers, armed with bright paints and brushes, decided to give these ancient figures a new lease on life!

It’s a bit like your grandma deciding to knit-paint neon crocs on the feet of that old family portrait — heartwarming, but historically questionable. These villagers, mostly in their golden years, saw the statues not just as relics of the past, but as active participants in their present lives.

Their painting was an act of devotion, a way of saying ‘thank you’ to the deities for answered prayers.

Chinese officials, of course, had a different perspective.

“Those villagers are all in their 70s or 80s. They said they painted the figures because they wanted to thank Buddhist for answering their prayers. For now, we can do nothing about this matter except criticising and educating them.”

Ah, nothing like berating old villagers on the cultural expectancies of the modern world.

Perhaps they could lecture them on their incorrect use of emojis, next.

👨🏫👵📱😠➡️👮♂️🤜💥😂🚑👍📈

But Were They Wrong?

I love museums. I love history. Plop me in a new country for a few days and I’ll inevitably end up reading at least 50 Wikipedia articles about the region I’m residing in.

It makes life interesting to taste interesting old life.

Hell, I even touched Hitler’s car once at the Canadian War Museum because I was a dumb curious kid who didn’t know a super loud alarm was attached (please don’t tell).

At least I was a fast runner back then.

But the thing about trancing around different geographies when I’m lucky enough to do so is noticing the vast changes that have taken place.

Pull up centuries old maps of a local city and you’ll often see it looks nothing like the modern layout, let alone the advent of sewers, freeways, MRTs, and what have you.

Because history is often not static.

After all, it’s told by the victors, and what we see with our eyes is not always what was present in the past.

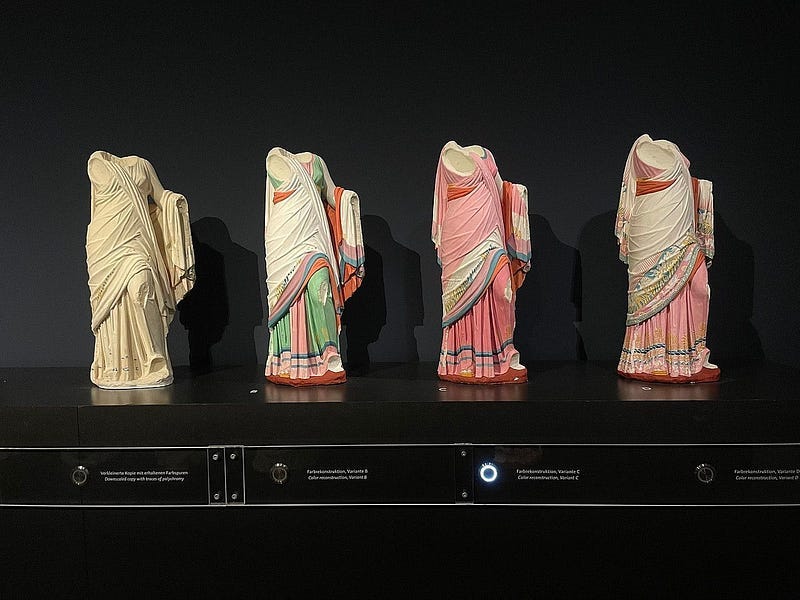

For years, we admired the beautiful marble craftmanship of the ancient Romans and Greeks. Yet, when confronted with evidence over time of their wonderful array of strange colorings, many historians balked at the idea.

“The whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is as well. Color contributes to beauty, but it is not beauty. Color should have a minor part in the consideration of beauty, because it is not (color) but structure that constitutes its essence” — Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “Father of art history”

It is hard to believe in what we cannot see for ourselves.

But to think of the ancients as not using any paint for their painstakingly crafted monuments and statues is unrealistic, to say the least.

Art and life imitate each other, and many of these deities, gods, and noble people who ended up eternalized through time were probably painted in the fashion of the time.

When the image of Cleopatra comes into mind, we think of elegance, beauty, silks, and eyeliner.

But pop the words “Cleopatra statue” into Google and we get a bunch of bland, albeit exquisite, monochrome figures.

Here’s what a reconstruction of what a Terracotta soldier would’ve looked like:

Not the earthy hues we’ve come to expect.

Just glance towards the Big Apple and you’ll see yet another, far more recent example.

After all, it’s not supposed to be green. The copper statue has just aged from oxygen and car-emitted sulfur.

What we, those still alive before the impending capitalism inspired demise of our environment, imagine in our minds when we hear the words Cleopatra, or terracotta soldiers, or The Statue of Liberty, is quite different from what our ancestors would conjure up.

What we, those still standing before the looming capitalism-inspired-demise of our environment, envision upon hearing the words Cleopatra, terracotta soldiers, or the Statue of Liberty, significantly diverges from the images our ancestors might have summoned.

And the same goes for those who survive the coming capocalypse well into the future.

Art and religion have no choice but to change with the times. It’s as natural as evolution.

Then again, perhaps that explains why this exists:

A “museum” that teaches children T. Rex lived alongside Adam…and was a vegetarian.

Sigh.

J.J. Pryor

👋Click the heart thingy? The algorithm loves it. I love it more.👋